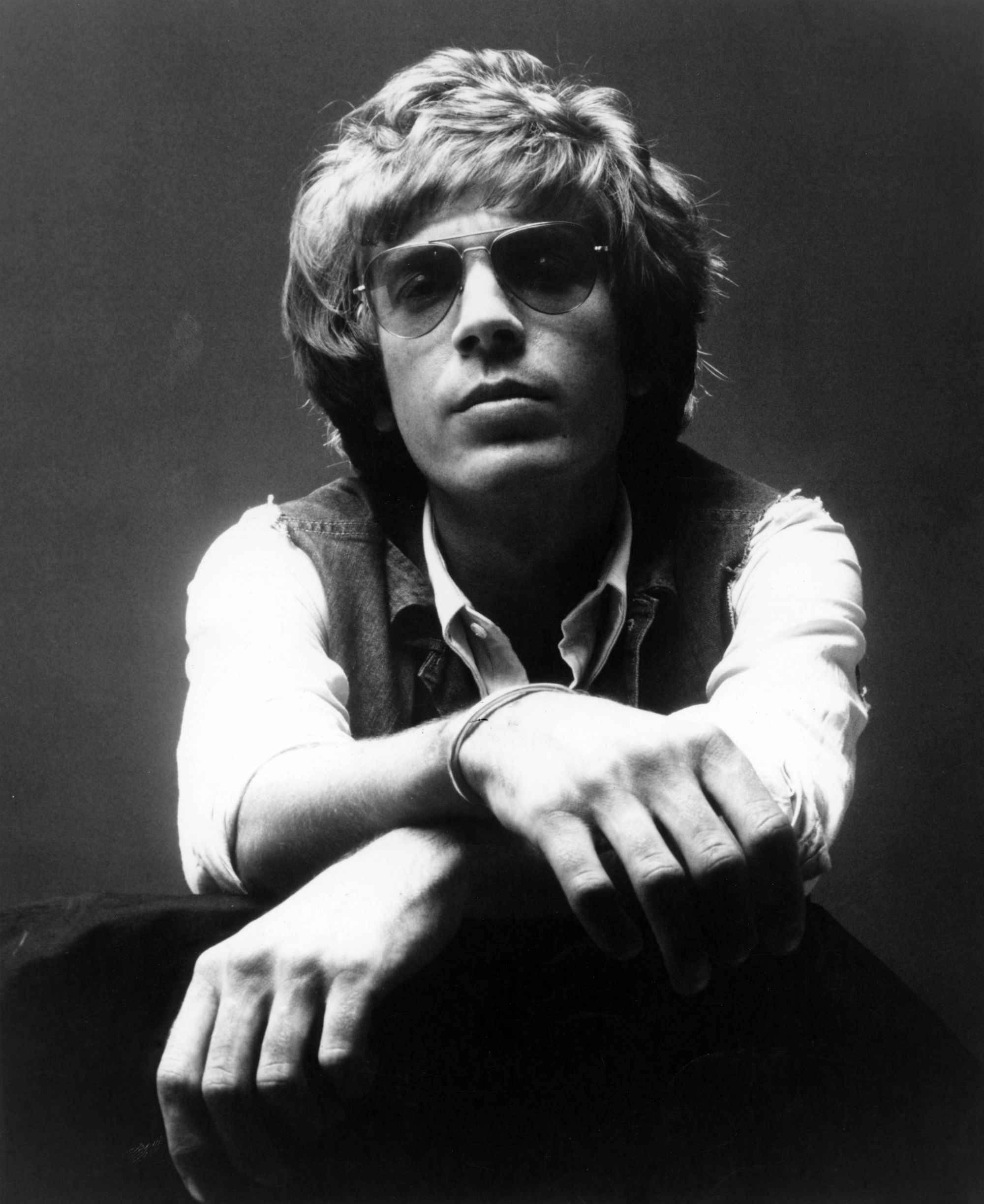

“One of the most enigmatic and influential figures in rock history”

Mark Savage, BBC

Noel Scott Engel (January 9, 1943 – March 22, 2019) better known by the stage name Scott Walker, was an American singer-songwriter, composer and record producer who lived most of his life in England.

Walker was known for his baritone voice and an unorthodox career path which took him from 1960s teen pop icon to 21st-century avant-garde musician.

Amongst attending art school and furthering his interests in cinema and literature, Scott played bass guitar proficiently enough to get session work in Los Angeles as a teenager.

In 1961, after playing with The Routers, he met guitarist and singer John Maus, who was using the stage name John Walker on a fake ID to enable him to perform in clubs while under age.

The two formed a band, Judy & the Gents, to back John Walker’s sister Judy Maus, before joining other musicians to tour as The Surfaris, although they did not play on the Surfaris’ records.

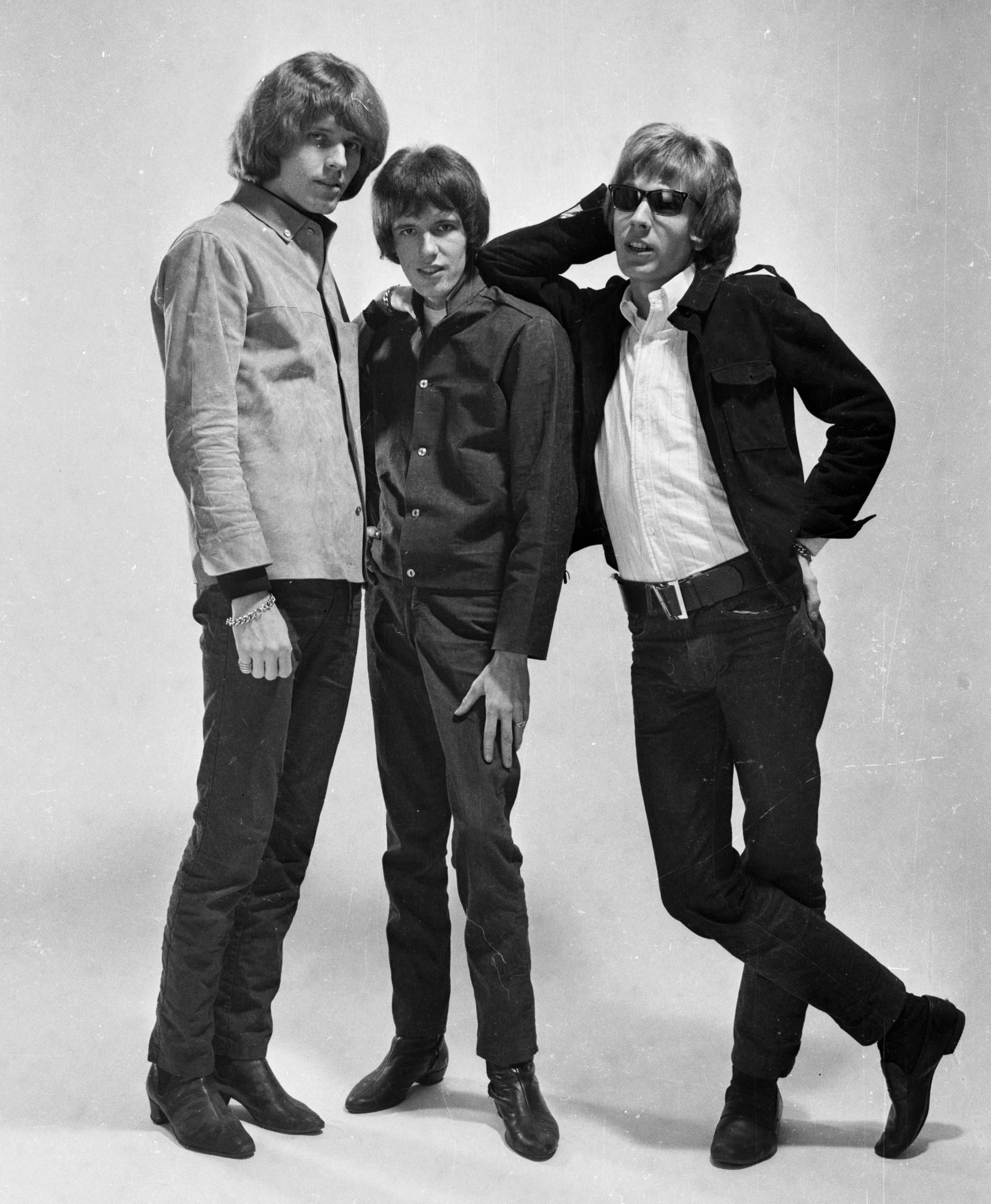

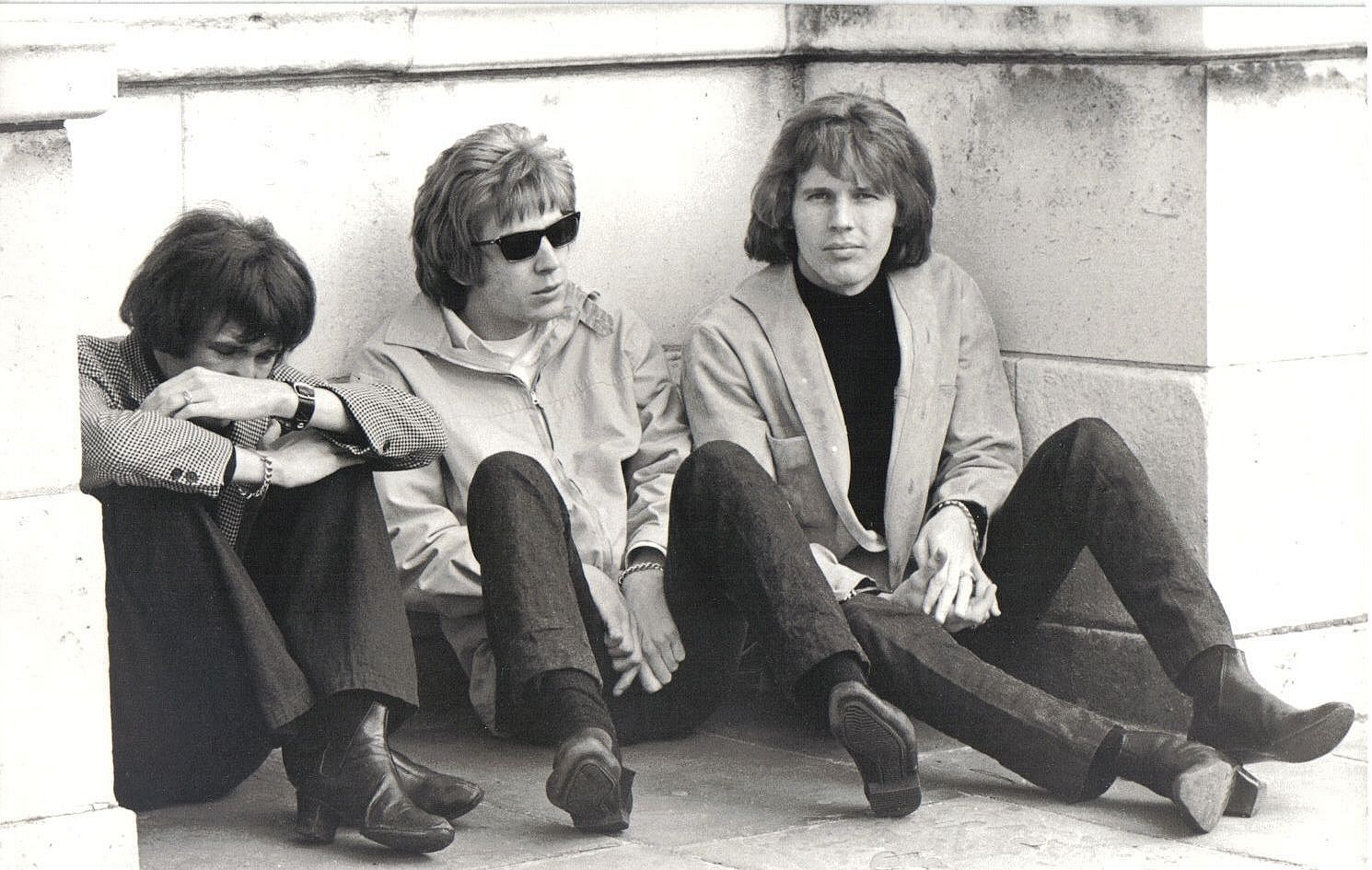

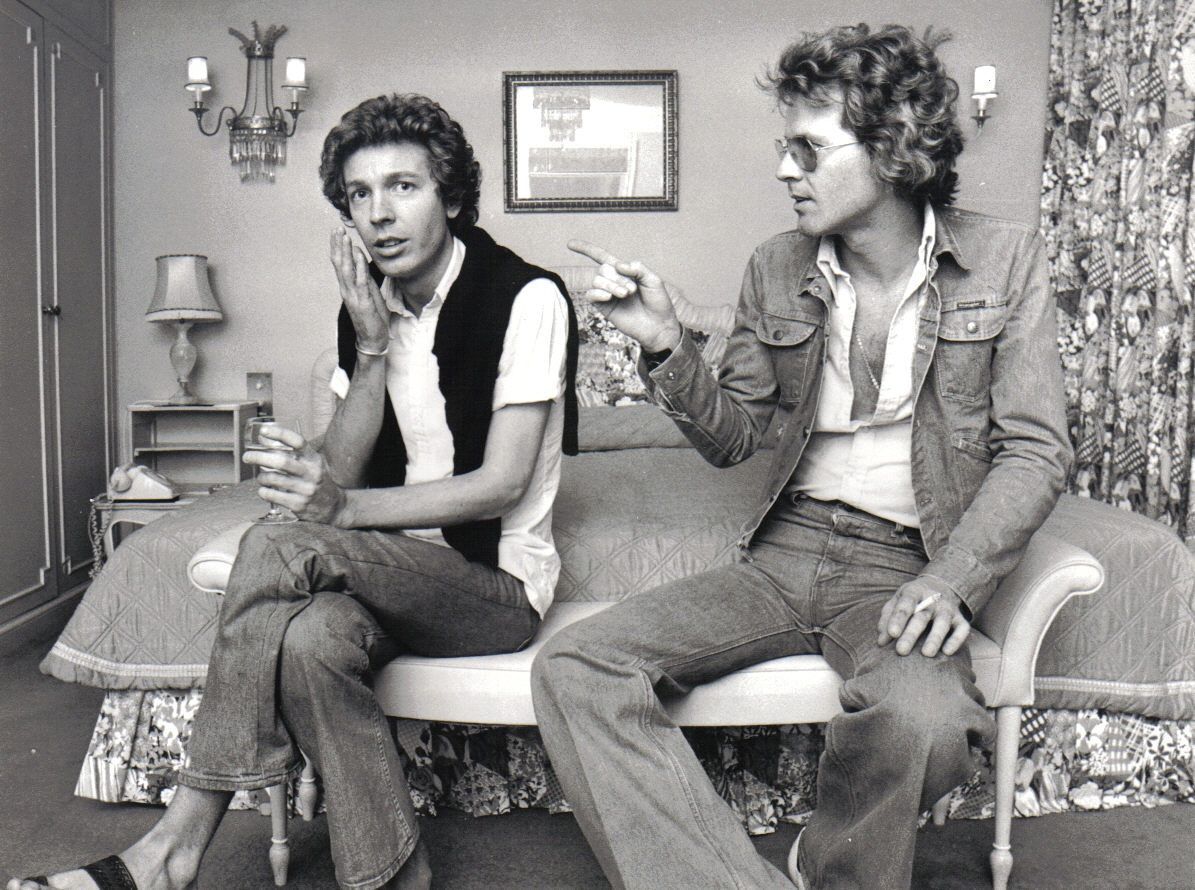

In early 1964, Engel and John Walker began working together as The Walker Brothers, later in the year linking up with drummer Gary Leeds whose father financed the trio’s first trip to the UK.

That was the beginning of the brief career of Noel Scott Engel with the melancholy orchestral-pop group The Walker Brothers, who for a couple of years in the mid-1960s were famous enough to be a front-cover concern on Tiger Beat magazine and have their car overturned by fans while they were still sitting in it.

As a trio, The Walker Brothers cultivated a glossy-haired and handsome familial image.

Prompted by Maus, each of the members took “Walker” as their stage surname.

Scott continued to use the name Walker thereafter, with the brief exception of returning to his birth name for the original release of his fifth solo album Scott 4, and in songwriting credits.

Initially, John served as guitarist and main lead singer of the trio, with Gary on drums and Scott playing bass guitar and mostly singing harmony vocals.

While working as a session drummer, Leeds had recently toured the United Kingdom with P.J. Proby, and persuaded both John and Scott to try their luck with him on the British pop scene.

The Walker Brothers arrived in London in early 1965.

Their first single, “Pretty Girls Everywhere” (with John still installed as lead singer) crept into the charts but did not place highly.

Their next single, “Love Her” – with Scott’s deeper baritone in the lead – was a more substantial chart hit and he became the group’s frontman.

Finding suitable material was always a problem.

The Walkers’ 1960s sound mixed Phil Spector’s “wall of sound” techniques with symphonic orchestrations featuring Britain’s top musicians and arrangers, notably Ivor Raymonde.

Scott served as effective co-producer of the band’s records throughout this period (alongside their named producer, Johnny Franz and engineer Peter Oliff), later described as a “parallel, if invisible Walker Brothers”.

By 1967, John Walker’s musical influence on the Walker Brothers had waned (although he sang lead on a cover of “Blueberry Hill” and contributed two original compositions), which led to tensions between him and Scott.

At the same time, Scott was finding the group a chafing experience:

“There was a lot of pressure. I was coming up with all the material for the boys, and I was having to find songs and getting the sessions together.

Everyone relied on me, and it just got on top of me. I think I just got irritated with it all”.

Scott Walker quickly became uncomfortable with this, and in 1967 went solo with four theatrical and increasingly dark albums, all called Scott.

Walker’s own relationship with fame, and the concentrated attention which it brought to him, remained a problem for his emotional well-being.

He became reclusive and increasingly distanced from his audience.

In 1968 he threw himself into an intense study of contemporary and classical music, which included a sojourn in Quarr Abbey, a Catholic Benedictine monastery in Ryde on the Isle of Wight, to study Gregorian chant, building on an interest in lieder and classical musical modes.

“GOING SOLO IN A MONASTERY!” a headline in Melody Maker read… a monastery Walker had to leave because fans started banging on the door looking for him.

The Scott albums remain part of a tradition of highly arranged, rock-free music that valued old songs over new sounds and professionalism over innovation.

“I don’t wanna see my fans walking around like drugged zombies,” Walker told a journalist around the time Scott came out in 1967, a rejection of the psychedelic culture prevalent at the time.

Instead, he embraced conventionally gorgeous, string-heavy music targeted at housewives and elderly people.

At the same time, he fell headlong into existentialist literature and European art-house cinema.

He appeared on variety shows, and remained either at or near the top of the charts.

He also developed a pitch-black sense of humor, and in his rich, mocking baritone explored songs about Soviet dictators and the spiritual poverty of men who only feel human in the company of whores (“Jackie”, the cover song of Jacques Brel released as a single in advance of Scott 2, was banned by the BBC).

If you look at the credits from Scott onward, what you see, essentially, is Walker taking over the show: on Scott, he wrote three songs among its 12, the rest covers; by Scott 4, he wrote them all.

Walker’s choice of covers essentially falls into two camps: Easygoing heartbreak music and songs by the Belgian writer Jacques Brel translated by Mort Shuman, who was also responsible for the hit musicalJacques Brel is Alive and Well and Living in Paris.

The latter’s impact on Walker can’t be understated : Walker covered him nine times on his first three albums, and some of the most elegant expressions of Walker’s romantic but poisoned worldview are his.

Walker’s own songs are more ambiguous.

From Scott 2, “The Amorous Humphrey Plugg” tells the story of a deflated husband who finds his peace of mind wandering thorugh the red-light district at night.

“Leave it all behind me,” he sings, sailing away on a tide of violins.

“Screaming kids on my knee and the telly swallowing me/ And the neighbors shouting next door/ And the subway trembling the rollerskate floor.”

Like good satire, Jacques Brel’s songs cue you to laugh then startle you with reality.

Walker puts you in the uncomfortable position of wondering whether to laugh in the first place, or to just lean back and allow these characters a glory that eludes them in their own lives.

At the peak of his fame in 1969, Walker was given his own BBC TV series, Scott, where he performed all your toe-tapping and heart-rending favorites in black sunglasses, without smiling.

By the same year Walker was writing epics about Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini and Robert Bresson movies featuring dissonant choir arrangements and trumpets blowing through canyons of reverb.

Released at the end of the year 1969, Scott 4 failed to chart and was deleted soon after.

It has been speculated that Walker’s decision to release the album under his birth name of Scott Engel contributed to its chart failure.

All subsequent reissues of the album have been released under his stage name.

Today Scott 4 is considered one of his strongest works and it has been praised by known artists such as David Bowie and the members of Radiohead.

The Walker Brothers reunited in 1975 to produce three albums.

But soon, the trio lost heart and interest, compounded by Scott’s increasing reluctance to sing live.

By the end of 1978, now without a record deal, the group drifted apart again and Scott Walker entered a three-year period of obscurity and no releases.

In the mid-’80s he began moving in a more experimental direction, shifting away from his penchant for pop standards of his own making and instead contributed to soundtracks and worked as a producer.

Scott Walker’s Climate of Hunter from 1984 furthered his movement towards the abstract (albeit very gradually), though it wasn’t until Tilt (1995) that his gift for radical songcraft and sound sculpting came to the fore.

If his earliest solo music contained unusual themes for a pop artist, they did at least contain fairly conventional orchestrations and melodies.

Tilt threw all that out in favor of a hybrid mixture of modern classical music, found sound, dissonant avant-rock, and hyper-personal vocal expression.

As a record producer and guest performer Scott Walker worked with a number of artists and bands, including Pulp, Ute Lemper, Sunn O))), and Bat For Lashes.

As legend has it, Sunn O))) approached Walker in 2009 with a blind call for collaboration.

He’d never heard them, but they hoped he’d pen something to sing for “Alice”, the orchestra-gilded finale of their 2009 LP, Monoliths & Dimensions.

Although he refused, he eventually converted to the band’s maximum-volume, minimum-movement metal.

He began writing new material with Greg Anderson, Stephen O’Malley with both their instrumental and thematic tones in mind.

Their collaborative LP Soused came out in 2014.

Scott Walker died at the age of 76 in London.

His record label 4AD announced cancer as the cause of death.

Tributes included those from Thom Yorke, Marc Almond, and Neil Hannon.

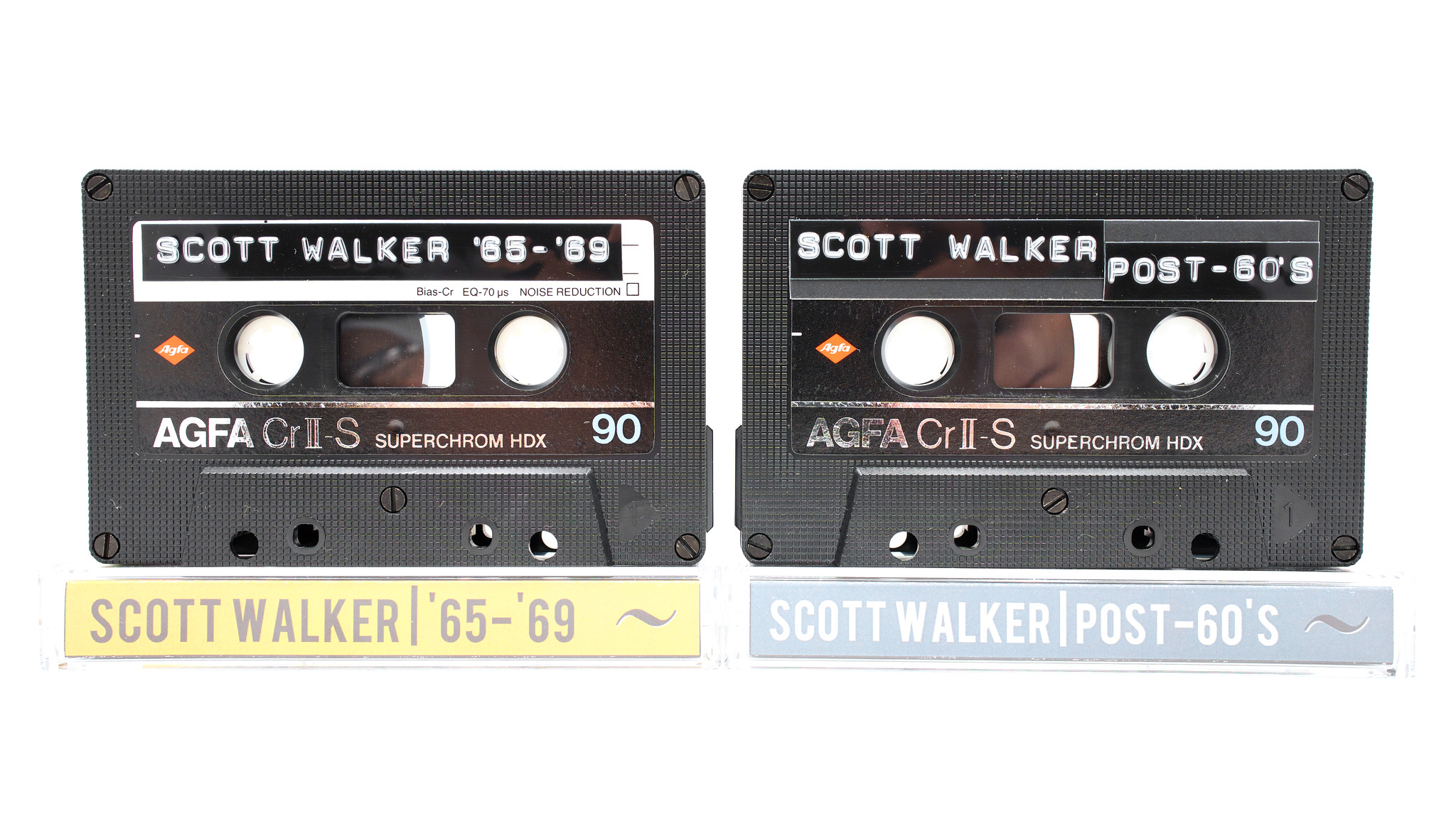

These two mixtapes are a tribute to the underrated genius Noel Scott Engel aka Scott Walker and his influence on many musicians and music enthusiasts over the years.

Requiescat in pace.

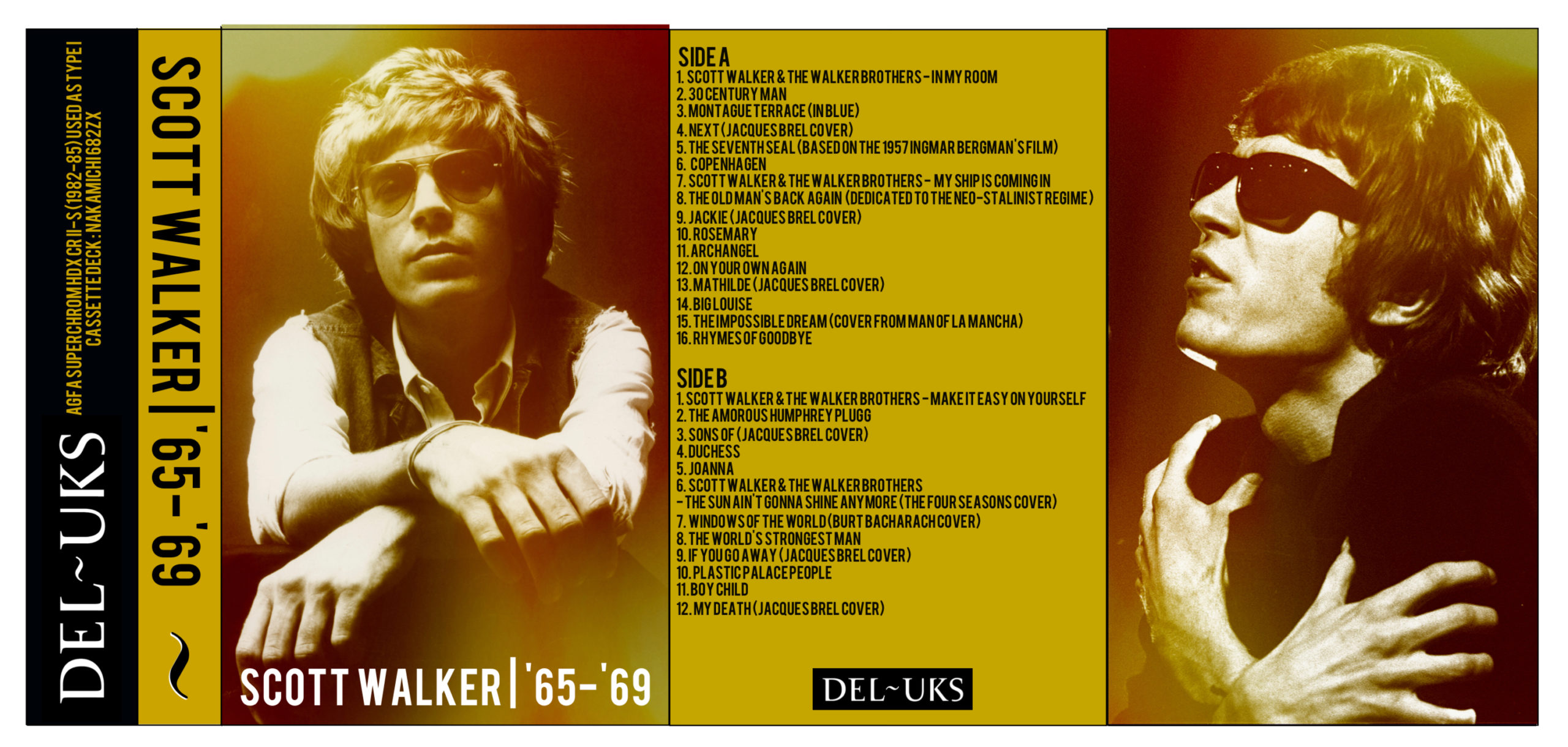

Mixtape 1 : Scott Walker | ’65-’69

For those who know Walker’s music through his avant-garde material from the last 20 years of his career, these highly arranged and orchestrated pop records seem to come from another world.

But the dark and strange themes were already there.

The essential contrast in his late-60s albums is between easy-listening music and forbiddingly difficult subject matter.

It’s a dichotomy that has always made Walker seem more like an outsider artist than a mainstream one.

Scott Walker | ’65-’69 Mixtape – Side A

Scott Walker | ’65-’69 Mixtape – Side B

DAW : Harrison Mixbus

D/A Converter : Schiit Bifrost 2

Analog Signal Flow : McIntosh MA-6200

Cassette Deck : Nakamichi 682zx

C-90 Cassette Tape used : Agfa Superchrom HDX Cr II-S (1982-85) used as Type I

Suggested Cassette Tape : Any 80’s/early 90’s Maxell, Sony or TDK C-90 Type I or II cassette tape (with extra time for both sides)

J-Card (.pdf)

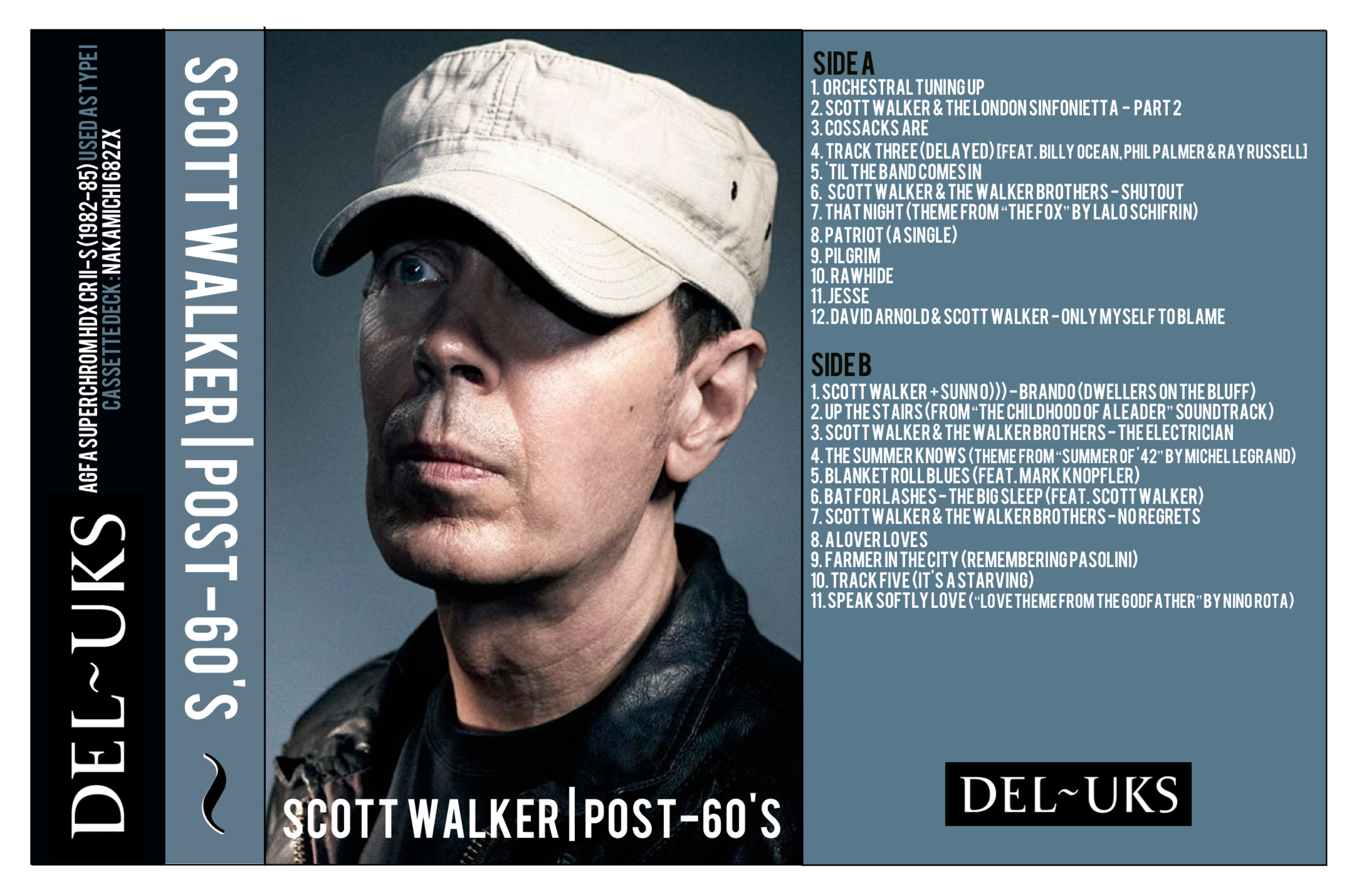

Mixtape 2 : Scott Walker | Post-60’s

Over the years, Scott Walker continued to push boundaries beyond musical genres with lyric-driven works which deconstructed music into elemental soundscapes.

Drawing on politics, war, plague, torture, and industrial harshness, Walker’s apocalyptic epics used silence as well as real-world effects and pared-back vocals to articulate the void.

Sometimes gothic and eerie, often sweepingly cinematic, always strikingly visual, his works reached for the inexpressible, emerging from space as yearnings in texture and dissonance.

Scott Walker | Post-60’s – Side A

Scott Walker | Post-60’s – Side B

DAW : Harrison Mixbus

D/A Converter : Schiit Bifrost 2

Analog Signal Flow : McIntosh MA-6200

Cassette Deck : Nakamichi 682zx

C-90 Cassette Tape used : Agfa Superchrom HDX Cr II-S (1982-85) used as Type I

Suggested Cassette Tape : Any 80’s/early 90’s Maxell, Sony or TDK C-90 Type I or II cassette tape (with extra time for both sides)

J-Card (.pdf)